“How does everyday life feel to you? Do the habits and routines of the day-to-day press down on you like a dull weight? Do they comfort you with their worn and tender familiarity, or do they pull irritably at you, rubbing your face in their lack of spontaneity and event?”

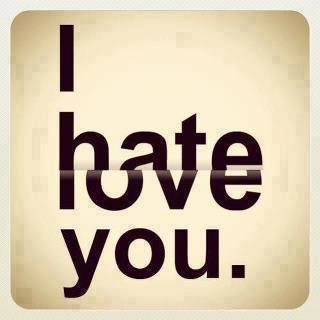

So asks cultural studies professor Ben Highmore at the start of his 2011 book, Ordinary Lives: Studies in the Everyday. My guess is that most of us would answer, “All of the above.”

Highmore’s provocative opening thus illuminates one of the basic ambiguities of the everyday: that we love it and hate it, intermittently, and all at once—when we’re not feeling neutral about it, that is.

We love parts of our routines (carrying a child downstairs in the morning) and hate others (waiting in a line of cars to drop the kids off at school). A healthy habit (exercise, a nutritious meal) feels like an accomplishment at one moment, an imposition at another. One EDLM diarist celebrates the availability of healthy, tasty food at lunchtime; at night, procuring snacks for his kids and their friends, it’s different: “The boys are hungry, so I swing by Little Caesar’s to pick up a pizza and some breadsticks before going home. I silently curse the fact that neither of those items are permitted in my new plant-based diet.”

We get sick of our routines. Then, when external events force us to break them, we get frantic or unsettled or resentful. A woman’s day starts with a person she has an appointment with showing up late. She records, sarcastically: “Well, because I’m such a patient and forgiving person (*deep eye roll*), let’s keep waiting and see what happens next.” Later on, stuck in traffic unexpectedly for forty minutes, she emotes plainly: “grunt.”

Then again, a break in routine—a weather delay in the school day—can feel like a gift from above: writes a schoolteacher, “I am heading to bed inordinately happy about that 2-hour delay!”

Sometimes we move from loving to hating everyday life in the same day, or in a single moment. Anyone who has raised a child can testify to the rapid toggling between tenderness and annoyance that can happen in the midst of caregiving, in the act of cutting up chicken nuggets, or changing a diaper, for what seems like the five-hundredth time.

We go on vacation—and to movies set in fantasy worlds of super-heroes, epochal battles, and narrow survivals—to escape from the everyday. But when the world outside gets too intense, perplexing, or exhausting, we long to escape to the everyday; to curl up on the couch with a pet and “watch bad TV” or take solace in our domestic routines.

If we’re depressed, the slightest everyday task may feel like drudgery. Or, getting one thing done might help us turn things around. “I’m going to take down my Christmas tree that has become a shadowy reminder of how little I accomplish when I’m depressed, making the depression worse of course” a diarist writes on Feb. 4. Later, having worked at it intermittently through the day, she finishes. “The Christmas tree is down!! Everything is put away!! I feel like I’ve conquered depression and lethargy!!”

Meanwhile, the optimists among us slough off irritation and boredom with positive self-talk. “Optimism is a courageous choice you make every day,” one diarist writes at the start of a Sunday full of errands, most of them on others’ behalf.

We are content. We are annoyed. We are neutral. For most of us, these feelings ebb and flow asymmetrically, mysterious as tides, but without their regularity. These waves, and their relative dominance of our individual lives, are influenced by factors like class and race, the work we do and the money we earn (or don’t earn, or can’t save), our relative comfort or precarity. But they aren’t reducible to those factors, either. Members of the working poor soldier on, buoyed by religious faith or a secular hope for a better day. Children of the professional classes suffer from depression or anxiety—each of which constitutes a distinct, and painful, relation to the everyday—and wind up on meds.

And it is one of the amazing aspects of human adaptability that almost anything can become everyday. Trapeze artists have routines; celebrities have everyday lives. A homeless man who spends his days begging and his nights beneath an overpass has an everyday life that he is used to—albeit one that is more precarious and less predictable than others. So does an astronaut.

In most of our everyday lives, death plays the role, at most, of a dark passing thought. In the everyday life of a hospice worker, or a funeral director, or a person with a terminal disease, death is everyday.

But I suspect that astronauts have boring days, and that homeless men have routine objects, places, and practices that comfort them, and that hospice workers have days when they love their jobs and weeks when they can’t wait for vacation.

When we keep our day diaries at Everyday Life in Middletown, we try to write down everything we do in one day, and what we were thinking and feeling as we did it. So the diaries register these vacillations between joy and disgruntlement with the ordinary.

But perhaps what they demonstrate more than anything is how much time we spend in a more neutral place—simply getting through the day without fuss. The diarist whose day began with the missed appointment recounts how a chance social exchange gave her a lift. Then she turns her attention back to her challenging day, without comment: “This morning just started off really crappy, but before I left, a woman complimented me on my tattoos and we had a short, nice conversation. Made me feel a little better. I’m at the soup kitchen now, waiting in line. I’m super tired.”

–Patrick Collier