“At home, B. shows me the old heater, charred and in pieces. He quickly installs the new device and no fish seem the worse off for any of it. If anything, the shark is being more social.”–Diarist A28, Nov. 24, 2017

The strange, the marvelous, is already present within everyday life. This was the claim of the Surrealists—a collaborative of artists in Europe and (later) America beginning in the 1920s. While we might know the Surrealists mainly through the much-circulated images of the painter Salvador Dali (those melting clocks), their shared project was very much aimed at everyday life, and they had strong and varying opinions about it.

Surrealism was, in part, an attack on rationalism. The Surrealists shared a sense that science, along with industrial and bureaucratic organization, had trained us to trudge through our days in a state of inattentive, muffled normality. Modern life had dulled our senses to the strangeness of the world before our eyes.

The Surrealists set out to counteract this habitual tedium in a number of ways. Among themselves, they played children’s games that produced jarring juxtapositions, like the famous “exquisite corpse”—a game in which a group of people write a sentence or draw a picture one word or panel at a time, none of them knowing what the others have produced. The game got its title when a round of this play produced the sentence, “The exquisite corpse drinks the new wine.”

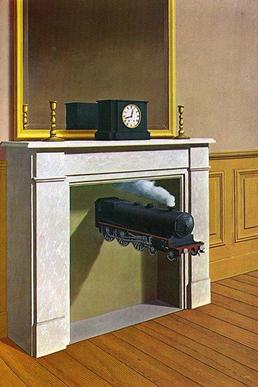

In paintings and sculptures, the Surrealists juxtaposed images in irrational ways. The irrational and the subconscious were sources of the strangeness that western culture had suppressed in us, they believed. Everyday items often appeared in these surrealist works: beans, bread, and clocks in Dali’s paintings, or the living-room mantle in Magritte’s famous “La durée poignardée (Time Transfixed)”

The point was two-fold: to make the everyday strange again through these weird juxtapositions and thereby to free people to recognize the strangeness already present in the everyday. We could find surreal juxtapositions in everyday life in places like a second-hand store, where an elephant’s-paw umbrella stand might sit next to a bass violin and some kitchenware; or in modern magazines, where advertisements for patent medicines, baby food, and motor oil might share a page with an image of a gorgeous fashion model. But our jaundiced modern eyes scanned such images without recognition. If we were dulled to such obvious strangeness, how would we ever notice the marvelous in more subtle forms?

All of this monotony helped to maintain the status quo, the Surrealists believed; they sought revolution, starting with consciousness. As the cultural theorist Ben Highmore writes, “The existence of the marvelous in the everyday was alienated from consciousness by forms of mental organization. What was needed was a systematic attack on such mental bureaucracy.”

The Everyday Life in Middletown diaries are not devoid of surrealist moments. And they could easily be made into grist for surrealist games. For instance, pick a word at random from a diary, then search a set of diaries on that word, and juxtapose the first three sentences you get.

I did so. I randomly selected the word “admit” and got this:

I will fully admit here that I also let him have the Ipad while he eats. When I told him let me smell your breath he admitted that he hadn’t. I admit I am confounded by this 40-hours a week thing.

In the Surrealist spirit, I am going to resist the urge to analyze that.

But I can’t resist the shark moment in the quote above. It comes near the end of an exhausting, busy day for Diarist A28. In the evening, the motor that warms the water in her tropical fish tank burns out. She has to run to the pet store, where she is vexed by a rude customer in front of her. On the way home she has a similar interaction in the McDonald’s drive-thru lane: “I get cut off by the car in the other line. Another glaring, cranky older woman.” She gets home to have her husband fix the fish tank, resulting in the surrealist gem that is the quote above.

The quote is surrealist in its juxtaposition of drastically diverse elements: 1) a shark, 2) the home, and 3) the notion of sociality. What could be further from the human or the social than the shark, a solitary hunter that has evolved just to the point where it became the most efficient killer and eater imaginable? And how strange is it—if we pause over it—to think of a shark living in the home of a middle-class, professional woman and her family, needing tending in the middle of a day overfilled with professional, community, and family obligations?

The juxtaposition makes me think about our own animal nature, and the everyday strangeness of our constant interactions with animals, whether they are our pets, the birds that lodge in the eaves of our house, or the insects that annoy us when we’re not ignoring them.

It makes me think of the predation that underlies almost all eating, raising the ghost of the pig that gave its life to stock our diarist’s slow cooker.

In this context, the nasty woman in the drive-thru line becomes a predator, moving through the shared habitat and competing with our heroine for food.

But beyond these darker resonances, the shark is also the recipient of our diarist’s caregiving, emphasizing is centrality to everyday life and its demands on us.

Caregiving is one of the major themes of the EDLM diaries, and is a major preoccupation of Diarist A28, whose day is bracketed with caregiving for her son, producing an unsurprising (but nonetheless touching) mix of exasperation and affection. A pork roast in the crock pot and that unscheduled trip through the drive-thru testify to the constant labor of feeding her family that is woven into her other obligations.

To have a social shark appear in the midst of all this is, well, marvelous.

–Patrick Collier