During the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic my father (now 82) began reading his travel journals out loud to my mother (now 86). His detailed accounts of their years of travel helped them cope with the likelihood that at their age, in a pandemic, their future travel would be limited.

Perhaps because of my father, from an early age I was fascinated with journaling. I began my first diary in 3rd grade. I was also allotted time during school to journal. My spiral CareBears-covered notebook is a mix of everyday musings and large-scale events. An entry about the Challenger explosion is bookended by talk of having a substitute teacher and my best friend telling me not to get bangs (she was right). As I got older, my journals became a means to work through complicated feelings. I filled volumes during my teen years, wrote hardly anything for years, and again filled up the pages when I went through divorce.

Yet, there is something uniquely attractive about not just recording the events: the national and personal tragedies, the vacations and celebrations. Recording everyday life helps put these events in perspective. For several years I engaged in a 365-photo project, taking pictures every day. In subsequent years, I used an app called “1 Second a Day” that splices together 1-second videos you take every day. And of course, I’ve now participated as a diarist in Everyday Life in Middletown, both lamenting and valuing the fact that diaries days corresponded with annoying or boring days. Doing so has led me to reflect on the way such projects influence my own memories.

Memory skews the way that humans perceive time. As we’ve seen many times in this blog, the pandemic highlighted this phenomenon for us. We perceive time as slower when we are younger because we are constantly recording and making memories that involve new information.

So, too, events are more memorable, and thus seem more influential than everyday life. Take, for example, a speaker you see who is particularly inspiring. Ultimately, how does one compare the influence of that person on your life to your colleague that you see in a mundane, everyday setting, but who you interact with nearly every day? Those big events—negative or positive—seem significant, in part, because they come with a great deal of new memory.

Seeing my everyday life flash before me in one-second videos from an entire year shifted my perspective on just how “big” those big events were. Rewatching my second-a-day videos, it struck me how little time the big events, like vacations take up. While I might have hundreds of vacation pictures, this format allowed me only 7—one per day of a week-long vacation. And when placed in the context of 359 other videos, the vacation seems small: overwhelmed by the people, places, and cats that I see every day.

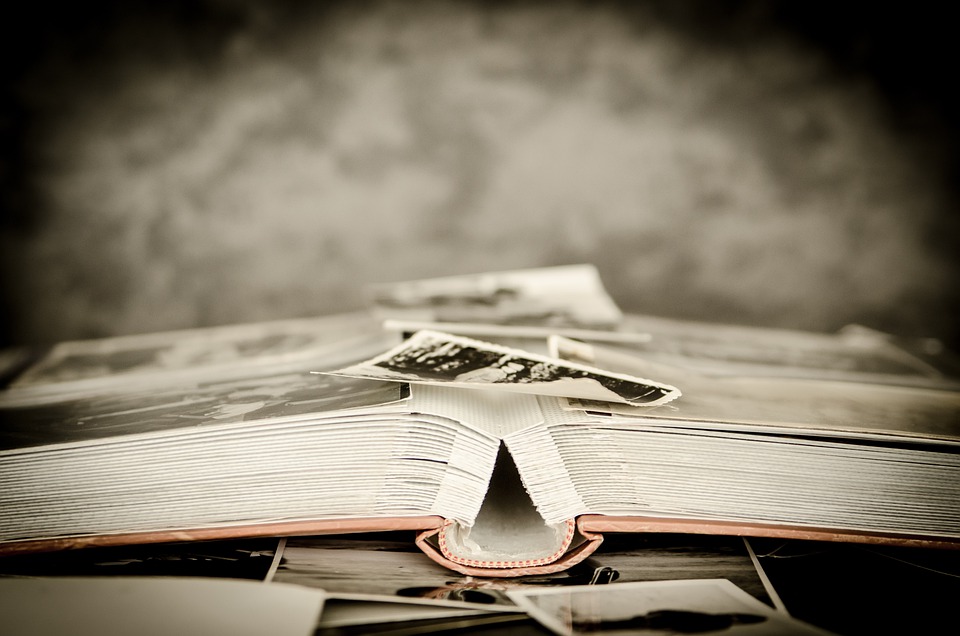

In her memoir, Darkroom: A Family Exposure, Jill Christman recalls her grandmother’s photo album and how carefully photos were selected to replace memory—to present one particular view of family life. So, too, Christman views her memoir as a shaping of memory. Authors spend years sifting through their lives and crafting their stories. While everyday journaling is certainly not devoid of such sculpting, recording a day as it happens (and submitting it a day or two later with little looking back) forms memory in a different way. I remember details from my diary days that I otherwise would have forgotten because I wrote about them and read about them.

Recording everyday life with others also connects us to collective memory in new ways. In “Writing diaries, reading diaries: The mechanics of memory,” Rebecca Steinitz calls diaries “disseminator of memory, making collective that which originates in the singular.” In the case of Everyday Middletown, I sometimes remember shared events that reoccurred in my journal and in the ones I read: a particularly gorgeous sunset, a news event that turned out to be fairly minor but seemed big that day, the fact that I am in good company with pizza Fridays.

It often seems that memories just happen to us with little rhyme or reason. Why can I remember details of that conversation with my boss but not my locker combination? How can my wife remember a bit of trivia but forget a basic chore? But memory is trainable, and it interacts deeply with how we experience our world. Daily journaling or other documenting efforts can shift our perspective on our life by focusing our memories differently. It’s about paying attention, retraining the focus and the memory to the everyday and not only the event.